Welcome!! If you’re yet to subscribe, kindly do so with this button. Also, remember to leave a like and a comment.

Dear Bolu,

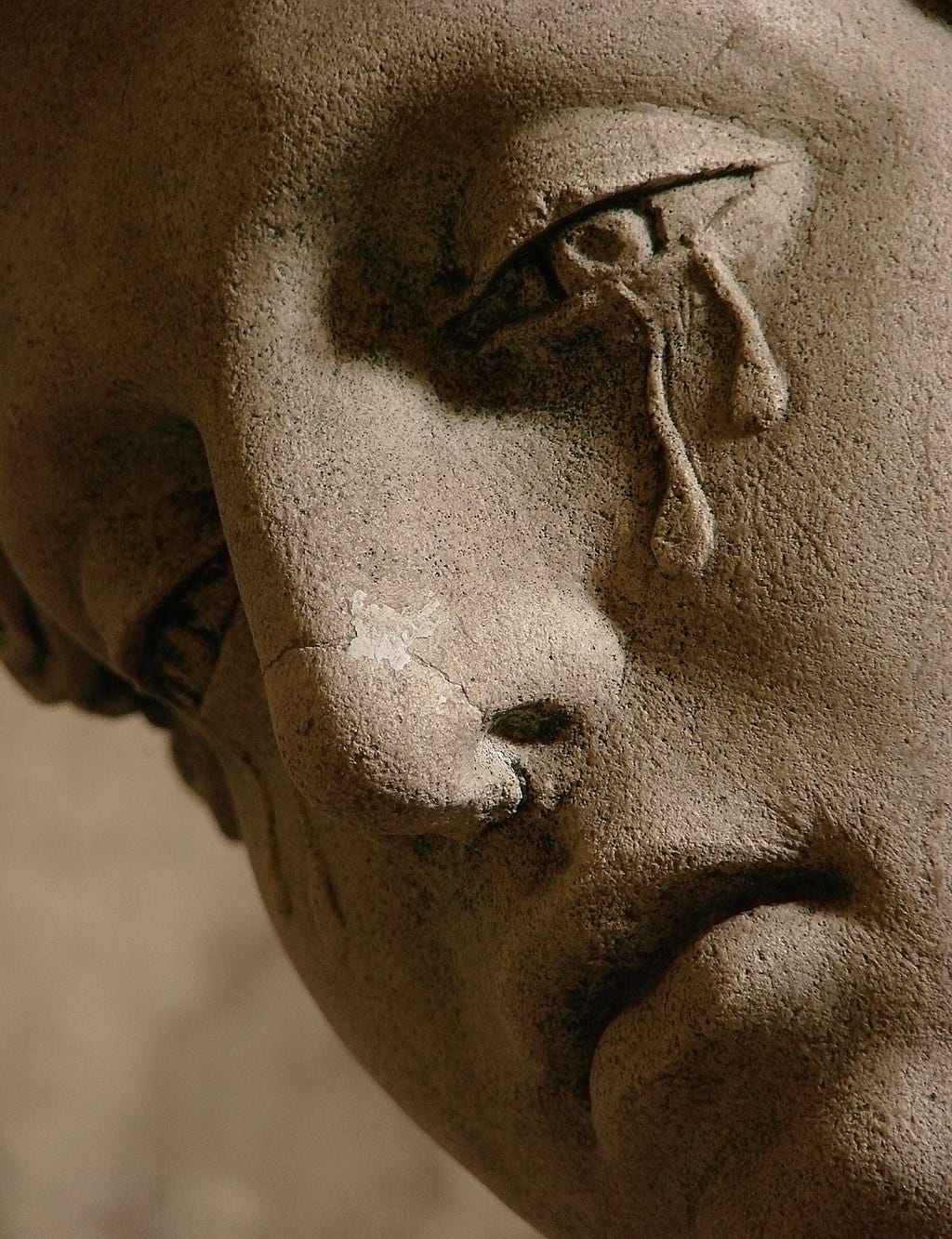

Bad news lurks and creeps up on us. It finds us in the middle of a pleasant dinner and rouses us from the arms of our lovers around 2 am. It stuns us in the boarding queue while doom scrolling on Twitter, and knocks on our door when we're least expecting guests. If it doesn't come today, you can bet that it'd come tomorrow. If you've not heard one recently, it's probably just stuck in traffic or on a quick detour to your friend's cabin. If we know too well that bad news will find us no matter what, why does it still surprise us? Perhaps it's simply our inherent optimistic nature. Perhaps it's the mistaken notion that we signed a deal with the universe that only good things would ever happen to us. If we are to ruin the surprise that accompanies bad news, we must learn to prepare for the worst. To be great receivers of bad news, we must go to bed accepting that that very night, a volcano would erupt and devastate the surrounding area. We must kiss our lovers goodbye, each time with the excitement that they're still ours and the resignation that tomorrow they'd be ours no more. We must open our mailboxes and watch social media posts expecting to see crisp details of an obituary scheduled for the following week or screenshots of the last scribblings of a suicide. If we're to be great at stomaching the worst of news, we must dwell, for a reasonable period each day, on the possibility that the ones we love the hardest or the things we desire the most will never again be within reach. Is this any way to live?

Now in the twilight of her life, she sits in the face of the evening breeze that blows past the waist-high burglary of the first-floor verandah. If she were fifty years younger, her choice of a blue cardigan on a multicoloured ankle-length buba would've warranted doubts about her sanity and discouraged suitors from coming to her bearing presents, promises, and poems. Now, she can dress however she likes. One of the good gifts of age, it seems, is the eyes that meet yours aren’t so judgy anymore. You can favour a pair of sandals over heels and not have the fashion police bother you. You can choose comfort over style and no one would call you a bad dresser. Abeni wears her cardigan every day, except on wash days. It doesn’t matter the beauty of the cloth underneath, it would get swallowed by this cardigan she got as a gift. It’s said that there are two kinds of special gifts—the first, we keep out of sight in a padlocked box underneath our beds, sandwiched between folded aso-okes, kaftans, and jalabiyas in the corner of our wardrobes or encircled by cobwebs in the deepest recesses of our attic. We let them see the sun only when there’s an occasion grande enough to adore and be adorned by them, or we want desperately for an old memory. The second, we wear on ourselves at all times—to the bath, dreamy wetlands, nightmarish caves, lunch dates, and client meetings. They’re never out of sight. They’re hung on the walls of our living room, conspicuously seated at the centre of our dining table, on the dashboard bopping to the music from the car radio, or dancing happily at our workstation. There are no prizes for guessing which of these two buckets you’d find Abeni’s cardigan. She always wore it. Opposite the house on the other side of the street, her eyes watch a teal Sienna slowly park. She may be old, but her eyesight is still good enough to recognize Baba Kekere's bumper-less minivan. The driver gets out of the car, and sure enough, it's her stepbrother. He's much younger than her, and of below-average height. The untidy pattern of scars and tribal marks on his face, and his short, springy legs conspire to tell the tale of a man who, in his youth, you could depend upon to jump into or out of a moving bus with complete abandon and leave any Goliath he faced on their backs. Abeni would have been glad to see him, but for the fact that she'd seen him only two days ago. Surprise visits usually end either very well or very badly and any rebellious cause for optimism is swiftly squashed when she sees the prophet of the local church get down from the passenger door. A shade of worry travels slowly across her wrinkled face, as her guests access the gate and make their way upstairs. "Baba Kekere, Woli…ṣe ko si laburu?" "Hope there's no problem?", she asks of her guests after a hurried exchange of pleasantries. "Rara rara, ko si nkan to jọ bẹ". "No no, there's no problem at all", is what she needs to hear from either man. It doesn't come. Instead, Baba Kekere takes off his cap to reveal a moist, shiny surface that you don't want to get headbutted with. "Ṣe rí, Mummy, ko si nkan nkan to n ṣẹlẹ laye yi ti o ye Ọlọrun…ṣe ẹ n gbọ mi ma?". "Mummy, you see, nothing happens in this world that God doesn't understand…are you listening ma?", he asks. She isn't listening. She knows what to expect. "Ki lo ṣe Mopelọla?" "What happened to Mopelọla?", she interjects. "Ọrọ Mopelọla ko le leyi". "This is not about Mopelola", is what she needs to hear. Again, it doesn't come. Abeni staggers quickly towards the feet of Baba Kekere. "Mummy e jọ, ẹ ni suru…ẹ joko". "Please, be patient, and have your seat", Baba Kekere and the prophet say. "Lekan, mi o ni suru o. Ki lo ṣe ọmọ mi?". "Lekan, I won't be patient. What happened to my daughter?", she says amidst the tears that have now replaced the worry on her face. Her brother obliges and confirms the reality of her deepest fears. Abeni screams. She throws herself in the direction of the balcony. "Kabiyesi Eledumare", is all the prophet can say. Baba Kekere does his best to keep her from hurling over. He's a strong man, but she's a broken woman. Abeni breaks in her blue cardigan, her daughter's last gift to her.

And for us the harbingers of bad news, should we seek an escape? For us, the face of distressing news, is there any consolation? We'd be forever associated with a sad memory, and it can't be helped. We're saddened by both the news we're about to give and the burden of this responsibility on us, and we cannot shrink from it. We may tremble as the words pour from our mouths—no, they don't pour, they drop bit by bit like water out of a broken spigot that never completely shuts. We're grave and solemn when we tell the rape victim is pregnant. We speak in a stern tone when we tell the 8-year-old boy he's lost his mom. We preface the news itself with, "I'm sorry", and we draw from our hopefully rich bank of euphemisms. We all get to play this role, in however little capacity. And the consolation, if any exists, is that it's a mark of courage, which, as Maya Angelou beautifully worded, is the most important of all the virtues.

The appeal of Chambre de Champs is, amongst other things, the illusion that you are alone even if the ten or so other tables in the diner are taken. One can see, through the transparent doors that enclose the cafe, souls that have sought each other out and lanterns of different shapes on the tables. You can't hear anything from the outside, but you can make out faces, moods, bored partners, gluttonous children, and impatient waiters. This evening, there's a couple close to the door. They've been seated for the better part of an hour, and they've ordered only coffee. You're right to suspect that they're here mostly for the conversation, and not so much for the food. They laugh, but it's half-contained as if they're trying hard not to make a memory of this moment. They talk a bit more. She hands him her phone, and he smiles with each swipe. What has she shown him? Incriminating screenshots? Their goofiest photos together? The coffee is cold, so they order more. He takes her hand in his, and the cafe is quiet. Unable to look her straight in the face, his eyes wander from the outfacing street to the champagne-shaped lantern on the table and back as he speaks and she nods her head. Mid-speech, she pulls her hand back to herself. She picks up her phone and makes quick work of pressing it. He finishes speaking, and she says a few words. Ten minutes pass without a lot happening. They stopped laughing a long time ago. Her phone rings as soon as a cab pulls up just outside the diner. She gets up to leave. They share a short hug and you hear it loud and clear—the sound of two broken hearts over four cold cups of coffee. In the cab, her head falls sideways on the passenger side window and his, on the doors of Chambre de Champs. The sky is clear. The clouds are white and the wind is dry but the air on both their faces is misty.

Nelly Furtado tempts melancholy when she asks why all good things come to an end. The temptation is potent because internally we're predisposed to thinking that if there's any justice in the world, good things should never perish. It's a malformed conviction because goodness is neither a precondition nor a guarantee of sustenance. The answer to Nelly's question, one will find, is unpleasant, unpalatable and insufficient. This ranks hers high as one of those questions that is good and yet, not too useful. I wager that rephrasing the question is a means to a more meaningful end. It's perhaps more helpful to ask why all things come to an end, and the answer, we'd find, is a shade clearer, a decibel louder, and more palatable. One needs only spend a moment observing the sunrise or pay closer attention to the butterflies we colour at sip-and-paint parties to grasp the answer. One could also find it in the air we breathe and the many bumps in antenatal classes.

Fin.

Thanks for reading! I’m delighted you made it here. If you liked this issue of Dear Bolu, you could sign up here so that new letters get sent directly to your inbox.

If you really liked it, do tell a friend about it.

Also, remember to leave a like or a comment!

Write you soon, merci!

- Wolemercy